Anatomy, Injury Patterns, Diagnosis and Initial Management

Disclaimer: This content is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice. Always consult your healthcare team before making decisions about your injury or treatment.

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears are one of the most devastating injuries an athlete can face. Unfortunately, they are also very common, with around 250,000 individuals in the US alone suffering this injury per year. In the United States, ACL reconstruction (ACLR) has been the gold standard of treatment for the past 30 years, and if you are an avid sports fan, you’ve seen professional athletes head straight into surgery within days of an ACL tear. However, surgery on its own may not be enough to address the consequences of this injury: only about two-thirds of athletes are successful in returning to their pre-injury level of sport, and many go on to experience ongoing knee pain or develop osteoarthritis in the years that follow their injury (Ardern et al., 2014). ACL injuries are one of the most researched injuries in surgical and rehabilitation journals, yet the outcomes are less than optimal. Understanding this injury and the importance of effective and progressive rehabilitation, are key to improving outcomes and returning to high level competition.

If you are reading this article, it is likely that you or a loved one has recently injured this structure. This is part I in a multi-part series designed to help you understand the ACL, how it is injured, and why that knowledge is essential for making informed decisions and maximizing your recovery. Subsequent posts will explore treatment options, rehabilitation strategies, and ways to safely return to sport, all with the goal of getting you the best outcome possible after this difficult injury.

What is the ACL?

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a ligament located deep inside the knee joint. Ligaments connect bone to bone, and the ACL specifically prevents the tibia (shin bone) from sliding forward relative to the femur (thigh bone) – a motion known as anterior translation. Although this motion is subtle, it is critical in keeping the knee stable, especially during intense sports movements like cutting, pivoting, and landing from a jump.

Other Important Knee Structures

Alongside the ACL, the knee contains several other important ligaments: the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), the medial collateral ligament (MCL), and the lateral collateral ligament (LCL). Another vital structure is the meniscus, which is not a ligament, but a C-shaped piece of cartilage that sits on top of the tibia, just below the ACL. The menisci act as shock absorbers and help evenly distribute forces across the knee when running and jumping.

Often, these structures can be injured alongside the ACL. When the ACL, MCL, and meniscus are all damaged simultaneously, it is called the “Unhappy Triad.” While many of these injuries also respond well to nonoperative care, they can add complexity to your recovery and may influence your decision on how to treat your injury.

How is the ACL Torn?

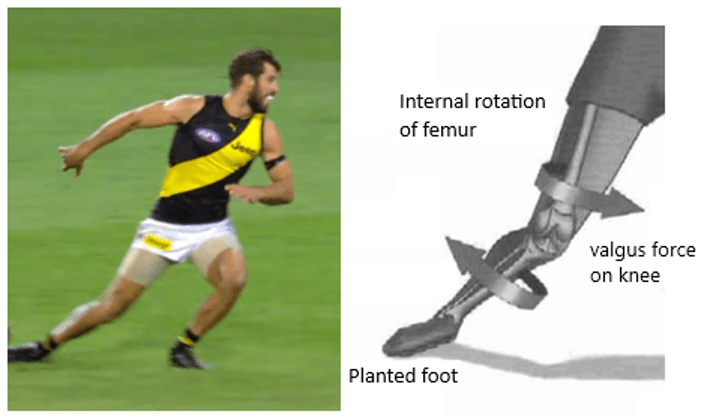

Most ACL injuries are non-contact, caused by sudden movements rather than collisions. Research shows that 70–80% of ACL tears happen when the knee buckles inward (valgus) during a jump, landing, or pivot. Even in sports like Rugby and American Football, the majority of ACL tears are non-contact.

Common injury patterns include:

- Sports injuries: early in the season when workloads increase; less experienced athletes are at higher risk

- Everyday accidents: awkward steps, trips, or falls can also tear the ACL

ACL injuries are often dramatic. Many report a sudden “pop” with immediate swelling, pain, or a sensation that the knee is “giving way.” Some athletes, however, can still walk or jog short distances before diagnosis.

Risk Factors for ACL injuries

The single biggest risk factor for an ACL injury is a history of a previous ACL injury. As a whole, the factors that lead to an ACL tear are multi-factorial and complex:

Biomechanical Factors:

- Dynamic knee valgus: The inward collapse of the knee during movements like landing or cutting. Some valgus is natural and necessary, but excessive or constrained valgus increases ACL stress.

- Landing or cutting with a stiff knee: A straight knee puts the ACL under high strain. Peak ACL load occurs between 20 and 40 degrees of knee flexion. Limiting flexion reduces the knee’s ability to absorb forces, increasing ACL stress.

- Muscle imbalances or weakness: Weak quadriceps, hamstrings, or hip muscles can compromise knee stability.

- Limited neuromuscular control: Athletes who are new to a sport or movement may have delayed or uncoordinated muscle activation, which can increase ACL stress. This ability improves with experience and practice, meaning proper training can reduce injury risk.

- Previous injuries: Prior ankle, knee, or hip injuries can create compensatory patterns that increase ACL stress.

Cultural Factors:

- Early specialization in a single sport: High training volume in one sport increases repetitive stress and overuse injuries, whereas diverse sports participation can reduce injury risk.

- Access to evidence-based injury prevention programs: Teams or clubs that do not implement structured neuromuscular training see higher ACL injury rates.

- Sex differences in youth play: Girls often have less exposure to competitive, organized sports at a young age compared to boys, which can limit neuromuscular development and contribute to higher ACL risk once they enter higher-level play.

- Sex differences in exposure strength training: Girls are not as encouraged as boys to participate in strength training, which may be a key in preventing ACL injuries.

Socioeconomic Factors:

- Limited access to high-quality training facilities or coaching: Athletes without resources may develop compensatory movement patterns or lack proper strength/flexibility programming.

- Healthcare access: Delays in evaluation, imaging, or physical therapy can worsen injuries, and subpar post-operative rehabilitation after surgery can lead to re-injury.

- Financial barriers to preventive care: Lack of ability to attend strength, conditioning, or injury-prevention programs may increase risk.

- Inequities in organized sports participation: Socioeconomic constraints may force athletes to play on suboptimal surfaces or with unsafe equipment, and ties back into financial barriers to preventative care.

ACL Symptoms and Diagnosis

Many individuals report a sudden pop and pain in the knee during a sporting move like a cut or landing from a jump. The knee will almost immediately swell, and most will report sensations of “giving way” or their knee buckling when trying to put weight on the injured side. Other symptoms include weakness and difficulty bending or straightening the knee.

A physical examination performed by a doctor, athletic trainer, or physical therapist can be very accurate in determining if an ACL injury is likely present. Regardless, almost all patients who report this mechanism of injury will be sent for an MRI of the knee, which can confirm the ACL tear and check for any other injuries inside the knee.

My MRI Confirmed an ACL Tear-Now What?

Your rally back starts the moment you are injured. Your initial management starts with these 3 steps:

- Achieve a “quiet knee”: Pain and swelling management are the first steps in your recovery. Elevate your knee above your heart (“Toes above your Nose”), ice frequently throughout the day, and use crutches to take weight off your knee to allow it to rest.

- Start “Prehabiliation”: As soon as you can, meet with a sports physical therapist who specializes in ACL injuries. They will guide you in achieving your “quiet knee”, start the process of getting your range of motion and strength back, and hopefully wean off crutches if cleared by your doctor.

- Decide to continue with non-operative treatment, or prep for surgery: Both are viable options for managing this injury, but the choice is highly personal and dependent on the goals, presentation, and preferences of each individual patient.

Conclusion

ACL injuries are complex, and recovery outcomes are closely tied to how the injury is managed from the start. Understanding the ACL’s role, how it is injured, and the factors that influence risk is the first step toward making informed decisions and setting yourself up for a strong recovery.

In Part II, we will dive more into the decision between surgery and non-operative management of ACL injuries.